I originally wrote this before the series on a 2d10 RPG, but I thought it was interesting for different reasons. And it's still true, even if I've settled on what I personally like.

I’ve been thinking a lot about table-top RPG mechanics

recently. There are a lot of different ones used, including roll-under,

roll-over, dice pool, and various combinations. For the moment, I’ll stick with

dice mechanics, and try to discuss the various pros-and-cons.

Why dice?

The first question to ask is why are there dice? Why do

role-playing games favor random dice rolls at all? It’s a useful question to

ask. Dice exist to turn collaborative story-telling into a game, letting an

objective arbiter (the dice) decide whether the player (including, sometimes,

the DM) succeeds or fails. It also adds risk/reward to allow the player to

attempt something where it’s not guaranteed that he’ll succeed.

It is possible to have a role-playing game without dice.

Sometimes an alternative source of randomness can be used (such as cards), and

sometimes no randomness is used at all. In that case, players succeed or fail

depending on their stats, and random chance doesn’t enter into it. In some

ways, videogame JRPGs often depend much more on the player and monster stats

than any random numbers (attacks almost always hit, damage is always within a

certain range), and overcoming non-monster obstacles depend much more on player

observational skills than any random number generation.

But a lot of that is that computer algorithms can, in their

complexity, give the appearance of randomness. It’s hard to predict what will

happen because the systems are hidden from us, and even when they aren’t,

they’re beyond our capacity to calculate quickly. Whereas, in table-top RPGs,

we want to keep the complexity of the calculation simple and the systems

up-front, so we allow dice to create the risk.

There are a number of different dice systems used in TTRPGs, but they can usually be categorized in the following ways.

Flat roll-over

Let’s start with a single die. You roll that die, add a

number based on your character’s stats, and check against a target number to

see if you succeed. The die is assumed to have flat probability distribution.

On a 20-sided die, you are as likely to roll a 1, or a 7, or an 11, or a 20. In

this system it’s easy to figure out what the probabilities are. Let’s say you

have a +3 on the roll and you need a 15. A 12 or higher will succeed, so you

have a 45% chance of success. The difficulty can be adjusted by changing the

target number. In Dungeons and Dragon, the target number is set by the DM, and

represents the difficulty of the task. However, there are other systems that are still flat roll-over systems.

Let’s take the Against the Darkmaster system. VsD uses a

d100 roll (this technically uses two dice, but since it still gives a flat

probability distribution, it’s equivalent to a single die). In most

circumstances, the target number is fixed at 100, which means that the

probability of success is the same as your bonus (a +30 bonus means you have a 30% probability of

success). Difficulty is determined by adding a penalty to the roll.

Flat roll-under

The converse of the roll-over system is the roll-under

system. This works very similarly to the above, except that you need to roll

under a value. In this case, the value is usually dependent on your skill. For

example, Call of Cthulhu and Warhammer Fantasy RPG both use a d100 roll-under

system, where your skill rating is the value you need to roll under. If you

have a 33 in a skill, you need to roll 33 or under. The GM can adjust the

difficulty by adding or subtracting from the target number. For example, a

routine check in WFRPG adds 20 to your skill rating and requires you to roll

under that (so 53 for that skill you have 33 in).

The advantage of the single die roll-over and roll-under is

that it’s easy to figure out the probabilities. Both for players (how likely am

I to succeed if I attempt this?), and for the GM (how hard should I make this if I want the player to be likely to succeed, but not guaranteed?). In this respect, Call

of Cthulhu and Warhammer are the easiest—you’re told the number you’re trying

to beat before you make the roll. But you don’t always want players to know

exactly what they need. D&D allows the DM to obscure this number by simply

not telling the players the target number they’re trying to reach.

Note that in both roll-over and roll-under, the higher the

number on the character sheet, the more likely it is for the player to succeed

on that task. This is in general good game design. Higher numbers being better

is intuitive for players.

However, one issue with both flat probability distribution systems is how swingy it is. The

20-sided die, or the d100 dice, give a much wider range of possible rolls than

the typical player character bonus. One way to address this, often explicitly

stated in books, is not to require rolls unless the situation calls for it. For

someone trained to ride a horse, most of the time he just rides the horse. But

if the horse is spooked by something, or he’s trying to win a horserace, or

running from the Wild Hunt, in that case, he should roll for it.

The issue is that in most games, there’s no difference

between someone trained in a skill and untrained unless you roll a die. And

when you do roll dice, the swinginess means that success or failure depends

more on the roll of the dice than your skill or training.

Summing dice pool

This has some of the advantages of the single-die roll-over,

but adds the complexity of multiple dice, which makes it very hard for players

and the DM to calculate the odds on the fly. Take the 3d6 roll. This is a

binomial probability distribution peaked around 10 and 11. 67% of the time,

this number is going to be somewhere in the range of 8 through 13. What this means

is that numbers outside of that range are very unlikely. There’s only about

0.5% chance of rolling a 3, and a 0.5% chance of rolling an 18. For people who

want most dice rolls to fall in a predictable range—who want something less

swingy than D&D—this is reassuring. Games like HERO and GURPS use a

roll-under version of this system (your stats set the target number you’re

trying to roll under), while games like AGE use a roll-over version of this

system (your stats set the bonus, and the GM determines the target number). I

worry that it’s easy to mess up in this system. A +1 or +2 to either the bonus

or the difficulty can have a significant effect on the probability, and it’s

easy for the GM to set target numbers that seem reasonable but are practically

impossible.

This system probably works better when it isn’t quite so

sharply peaked. A more reasonable version is the 2d6 system used in Powered by

the Apocalypse, a system used in a number of games, including Apocalypse World,

Dungeon World, Monster of the Week, and Avatar: The Last Airbender RPG. In this

system, rolling less than a 7 is a failure, 7-9 is a success with a

complication, and 10+ is a full success. Player stats give them somewhere

between a -1 and a +3 modifier, and the GM can determine that the situation

gives them a penalty or a bonus. While this isn’t as sharply peaked as 3d6, you

still have a 58% chance to roll a 7 or higher, and a +3 means that you’re more

likely than not to roll a complete success.

Usually the number of dice you roll in a summing dice pool

is fixed, but some systems allow you to roll more depending on your character

stats. This can lead to huge differentials between skilled and unskilled

characters. The One Ring uses a version of this, but its mechanics make this

less of a problem than something like West End Games’ old Star Wars RPG, which

often saw a huge difference between normal and Force-using characters due to

using this mechanic. Arguably this was the desired effect, but it messed with

game balance.

Counting dice pool

In this system, you roll a number of dice and count the number which meet a requirement, the number of sixes, or above a certain value.

This system has a number of advantages. The first is that

it’s generally easier for players to roll a bunch of dice and on-the-fly count

the number of sixes than to add up all the numbers on the dice. Also, it’s

generally easier to figure out the odds of success or failure than for a

summing dice pool, though not as easy as for a flat roll-over or roll-under

system.

Systems based on this include the World of Darkness games

(Vampire the Masquerade, Mage the Ascension, etc.) and Shadowrun. What these

games have in common is needing a number of dice to match the criteria, and

counting those dice and comparing them against the number required to

successfully complete the task. For now, I’m leaving out those games where the

number necessary is one—those fall under the next version.

One of dice pool

Under this system I include all those systems where you need

to roll multiple dice, but only use one of them. Some of these could

alternatively be considered under the counting dice pool system, but you only

need one success. Some RPG systems that generally fall under another system

have subsystems that fall under this mechanic: fifth-edition D&D has the

advantage (roll 2d20, take the highest) and disadvantage (roll 2d20, take the

lowest) mechanic to handle different situations the character faces.

Games like Blades in the Dark, Lasers and Feelings, and the

Free League Year Zero games (Mutant Year Zero and Vaesen, for example), use

this. Some are more like counting dice pools, and some are more like flat roll

over, but the addition of the best of dice pool mechanic increases the odds of

success. Calculating those odds are usually not too difficult.

Another game that falls under this is Savage Worlds,

although that’s inherently more complex. There your character stats affect the

type of die you use (d4, d6, d8, d10, and d12), but you also always roll a

Wildcard die (a d6). This makes it more of a best of system, though it’s

generally a flat roll-over, where you’re always trying to get a 4 or higher,

but mechanics such as exploding dice, modifiers on the die results (-4, -2, +2,

etc.), and multiple dice for certain actions, can certainly add to the complexity.

Finally, some systems don’t use the best die. For example,

the Sentinel superhero RPG has you roll 3 dice, whose types depend on the

character stats and the situation, and take the middle roll. As it’s a

superhero game, different powers can have you using the highest or lowest rolls

to have different effects.

Compound systems

Finally, some systems use a combination of these mechanics

for basic task resolution. Both the Warhammer: Age of Sigmar Soulbound RPG and

the Modiphius 2d20 RPGs (Conan, Star Trek, etc.) combine a counting dice pool

with a flat roll-over/under mechanic. In Soulbound, your stats determine the

number of dice you roll, but different tasks can have different target numbers

for each successful dice and a different number of successes required.

Meanwhile, 2d20 has a roll-under mechanic, where your stats set the target

number for each successful roll on a d20, and the situation can determine how

many successes you need, and how many dice you can roll.

These systems tend to be very flexible, but also very

complex to figure out odds. Where it’s spelled out in the rules (for Soulbound,

situations such as spellcasting and combat have clearly set target numbers and

success count effects), you can hope that the developers have figured out how

to best balance the system. But on the fly calculations are much more

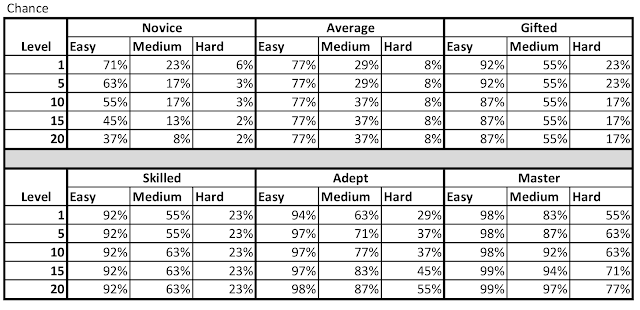

difficult, and hopefully the developers have at least provided a table to make

it easy for the gamemaster to figure out.

Conclusion

So I bring up all these systems to give you an idea of

what’s available, both in case you’re looking for a system to play, and you’re

considering developing a system. I’ve thought about it a bit, and here are my

thoughts on what should go into developing a system:

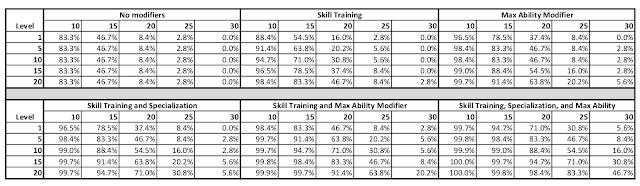

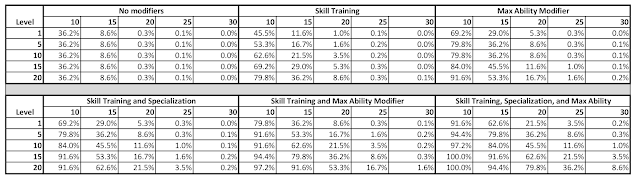

· Consider how often you want

the characters to succeed rather than fail. D&D is balanced around the idea

that for an easy task (DC 10), even the least qualified player character should

succeed about half the time, while the most qualified character succeeds about

80% of the time. As you level up, the most qualified character succeeds more

often, and can take on more difficult tasks with a reasonable chance of success

(a tenth level character with proficiency and a maxed out attribute would

succeed at DC 20 50% of the time), while the least qualified character doesn’t

improve. For this reason, specialization is important in D&D, and most

parties have at least one specialist for each common situation. In combat, the odds seem to be built around a 65% chance to hit with an attack.

· Consider how often

extraordinary successes or failures happen. Do you have critical successes and

failures? How often do you want them to happen? Some games use exploding dice (Savage

Worlds, Against the Darkmaster), where if you roll high enough or low enough,

you roll again and add it (or subtract it!) from the total, and consider an

extraordinary success to be a particularly high roll, something that usually

only happens when the dice explode. Other games have special rules for

adjudicating certain rolls on the dice (D&D’s critical successes and

failures on a 20 and a 1, and the One Ring’s Gandalf and Eye of Sauron die

faces). With a summing dice pool, really low and high rolls become less common,

so you may have to set the odds carefully to get these extraordinary successes

and failures regularly.

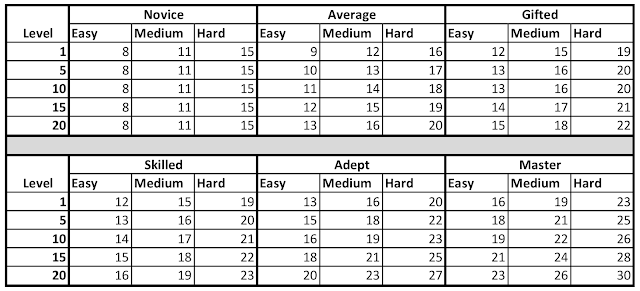

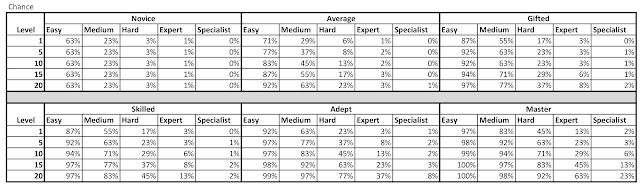

· Consider what’s easy for

both the Gamemaster and players to adjudicate on the fly. PCs don’t need to

know the exact odds, but they should have a general idea of what their

characters are good at, and when the odds are for or against them. Gamemasters

often need to set the difficulty, and for that, they should have a good idea of

what the odds of success or failure are for their characters.