In my first post on this topic, I talked about 2d10 as a variant for Dungeons and Dragons, and focused on the ways it interacted with its existing systems. Because of that, I limited how far I used things such as degrees of success. Now that I'm considering, because of the OGL mess, how I would build a system around 2d10, I'm rethinking how I did things in that post, and the subsequent Weal and Woe pools.

Math First

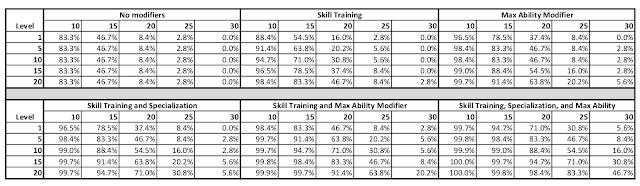

First, let's take a step back and consider how much effect do you get from rolling an extra die (3d10), and then selecting the best or worst two. Let's revisit this table from my Abilities and Skills post:

|

| Odds of rolling different targets with 2d10 at different levels of ability. |

As you can see, even with no training a character would usually pass a test with a target number of 10, a character with either a maximum ability modifier or skill training and specialization (which will give a similar result as those with decent Skill Training and a decent ability score) have a good chance of succeeding on a Medium test, and those with all three have a good chance of meeting a target number of 20 at low levels (but those with only one or two of Skill Training, Specialization, or maximum ability modifier become more likely to reach it at higher levels).

Target numbers of 25 or above are basically there to give those who have mastered a skill something more challenging at higher levels. A target of 30 is almost impossible--it should only be attempted at high levels, and adventures shouldn't hinge on successfully making that check. In some ways, 25 and 30 are more useful to show the odds of the most capable character getting one or two extra successes versus DC 20.

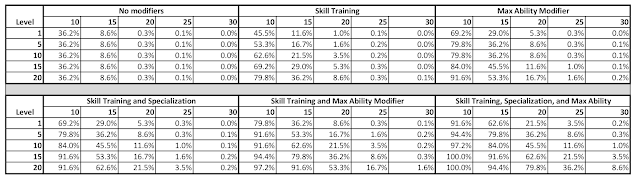

So that's what it looks like if you're only rolling two dice. What if you're rolling three and taking the two best. Then, your odds of success look something like this:

|

| Odds of rolling different targets with 3d10 keeping the two best at different levels of ability. |

This makes the higher targets of 25 or 30 look more achievable, as low odds basically double (high odds only change incrementally).

What if you're stuck with the two worst? That looks something like this:

|

| Odds of rolling different targets with 3d10 keeping the two worst at different levels of ability. |

Now really high rolls look practically impossible. Most of the odds that were less than 50% before are effectively cut in half. This suggests that target numbers of 25 and even 30 at high levels are something you should only throw at your players when they attempt something ill-considered and you expect them to fail--but you want to give them a chance to do something epic if they succeed.

Weal and Woe, Mostly Woe

So we want the probability shifting that comes from throwing an extra die, but we probably want to call it something different from Weal and Woe, which is what I was using earlier. I suggest that when a player rolls an extra die, you call it a Fortune die, and when the GM rolls the extra die, you call it a Doom die. This applies no matter what circumstance grants it (spells, favorable or unfavorable circumstances, aid from another party member). The reason for this is that I want to keep my Weal and Woe Fortune and Doom Pools as an optional element, and if we have a mechanic called Fortune dice, we can easily add the idea of a Fortune Pool, as the resource from which those Fortune dice come.

We can also give each player character a fortune point, similar to D&D's inspiration. They can gain a Fortune Point whenever they roll doubles, and spend them to roll a Fortune die. Note that unlike the Advantage/Disadvantage, spending a die for Fortune has no effect on whether the DM rolls a Doom die. You merely have to declare you're doing so before the DM discards a die, and then you each roll, and remove a die in the order you roll.

Degrees and Doubles

In my first post introducing the 2d10 mechanic to D&D, I included two mechanics that interacted with one another, doubles and degrees of success. I stipulated that degrees of success only applied to ability checks, while doubles applied to all rolls that would use a d20 in D&D (including attacks and saves), and had to explain how to handle doubles in each situation.

That said, if I'm creating my own system more or less from scratch, I don't have to adapt it to how D&D handles different types of d20 rolls. That allows me to smooth things out more and make it more consistent. So let's adjust things this way: all rolls have degrees of success and failure. This includes attack rolls, saving throws, and ability checks (though since they're all the same, we no longer need to divide them up this way).

So an attack roll can have one, two, three, or more degrees of success, while a saving throw can have one, two, or three degrees of failure.

That also lets us approach high doubles and low doubles differently. A high double increases your degree of success by one, while a low double decreases your degree of success by one. However, universally, degrees of success and failure are every 5 points above or below the target number. Therefore, it may be easier to treat a high double as adding five to your roll, and a low double of subtracting five from your roll. This results in moving you up and down the success ladder the same, and may be easier to remember. (And it's definitely useful for doing opposed rolls, where a double could change who wins.)

We can also use the skill descriptions to describe what various degrees of success mean for different skills, and spell descriptions for what degrees of failure mean for saving throws (it might be useful to take a look at Mutants & Masterminds, which does this already for a lot of its abilities, with certain conditions being stronger versions of other conditions, so that when you fail against an attack that applies a condition, the degree of failure determines which condition applies).

One thing to think about more in-depth is the concept of zero degrees of success, or a Near Miss. In many contexts, this is simply a failure with no additional consequences. You failed to pick the lock, you missed the enemy, etc. But I'd like to encourage GM's to allow it to be a success with consequences, or at a price. This is especially the case for high, almost impossible to achieve target numbers (anything higher than 20 for most parties). If it's very hard for your PCs to reach the target number, there's still a decent chance of almost making it. In that case, it may be worthwhile to let them have it, but at a price.

So here are some ways GMs can use a Near Miss:

- A failure with no additional consequence. You don't convince the king, but you don't offend him either. You don't find the evidence you were looking for, but you can keep looking. You miss the enemy, but assuming he doesn't kill you in the meantime, you can try again next round.

- A partial success. You try to grab the gold, but only get a few coins. You try to catch the falling potions, but only rescue one. In these cases you did part of what you were trying to do, but not all.

- A success, but it takes ten times as long. This is particularly useful in a situation where the character can simply try again. It's less interesting to have the player roll multiple attempts than it is for the GM to just declare that they succeed, but it takes a while. Especially when the GM uses this to increase tension. What would have taken a round on a success instead takes a minute. What would have taken a minute takes ten minutes. What would have taken an hour takes all day. GMs should always present it as a choice: "After a minute of poking at the lock, it's clear this is going to take a while. Are you going to keep at it, knowing that a patrol may come by at any minute?" Then the GM uses a random roll to determine whether the patrol arrives, using their favorite method to determine if a random encounter happens.

- A success with a consequence. You succeed, but something bad happens as well. You get the lock open, but made enough noise to attract a guard in the meantime. You convinced the king that there's a problem, but his solution is not one you like. You avoid the pit trap, but now your party is separated by it with no way to reconnect. In general, you don't want the consequence to be worse than what would have happened with a degree of failure. GMs don't usually need to give the players a choice to use this option.

- A success at a price. You succeed, if you're willing to pay the price. That price may be gold to pay the guard, or a level of Stress, or a valuable item falling from your pack to the jagged rocks below the cliff you're climbing. In this case, the GM should present this as a choice.

Stress

Many games have different pools for different types of injury. Consider for example the Warhammer Age of Sigmar RPG Soulbound. This has Toughness (an HP pool which you recover after every battle), and Wounds (more significant injuries that take time to recover from). D&D doesn't exactly do this, but the exhaustion mechanic (and especially the one introduced in One D&D) gives us an ability to give players conditions that affect their performance and that take time to recover from. Many tables use the exhaustion mechanic to introduce penalties when players lose all their HP and go down and need to be healed to get back on their feet. With the 5e version, that is very punishing.

But I do think I want something along these lines. Let's call it Stress for now. You receive a level of Stress whenever you go down to 0 HP in combat. It can also be the price you pay to turn a Near Miss to a success, or if you fail an important roll (say you're traveling in a hostile environment and fail your Survival check), or it could represent an injury you receive from a trap. For each level of Stress, you subtract 1 from all your rolls, and when you exceed the maximum, you're down for good. This can mean dead, or just collapsed, unable to get up again.

In One D&D the maximum number of exhaustion levels one can reach is equal to 10; after that you die. I think I'd make that something dependent on the character stats. For example, you can make the maximum equal to the character's Fortitude + Will ability modifiers, but you would need a minimum value for players who decide to dump both Fortitude and Will. I would say if you have 0 in an ability score, you can use 1 instead. (So if you have Fortitude of 3 and Will of 0, you'd have 4 Stress Levels.)

Recharging

D&D 4th edition had at-will, encounter, and daily abilities, and encounter abilities would recharge after each battle. As a whole, people didn't like it. But recently, I've played a number of video games with a similar mechanic, such as Chained Echoes and Pillars of Eternity 2. I like how you can go from battle to battle, and only worry about retreating when you gain wounds which you don't recover from quickly. From tabletop games, I'm inspired by the Soulbound Toughness and Wound mechanics mentioned above, and by the spell point mechanic used in Aetaltis, a D&D 5e campaign. In Aetaltis, spell points recharge, and you regain a number of them every hour.

A Stress, wounds, or whatever I decide to call it gives me a more durable mechanic for injury, that comes with a built-in penalty to rolls. So on top of that, I can have a hit point pool that recharges rapidly after a battle. For spell points, I can have those recharge at a rate dependent on Will and class every hour. This will require a smaller maximum number of spell points compared to spell slots. In general, it'll probably be more spells at low levels, and fewer at high levels, with spell points allowing a few high level spells to be cast or a number of low level spells.

I'll talk about my ideas for magic in a later post.

No comments:

Post a Comment

I moderate comments on posts more than a week old. Your comment will appear immediately on new posts, or as soon as I get a chance to review it for older posts.